My take on Net Neutrality

Published Wed Nov 08 2017 07:01:00 GMT+0000 (Coordinated Universal Time)

Tech

Introduction

The Internet’s unique architecture has enabled it to rapidly expand its influence on our world. Within a relatively short period of time, it has become a vast network which gives every user instant access to a wealth of knowledge, opinion, debate, innovation, and choice. It has been able to foster ideas and drive innovation thanks to its uniquely open and decentralised nature [14] - a model which differs greatly from the architectures of traditional telecommunication networks [2]. It has changed the way in which many industries and businesses operate, and the way consumers live. Net Neutrality (NN) has played an important part in allowing this change to come about by maintaining the Internet’s openness at a time when Internet Service Providers (ISPs) could control everything at the network-level.The Internet’s impact on the World Wide Web (WWW) itself has been no exception. Since its invention, the WWW has changed beyond recognition. Once a system for accessing simple documents, the web now allows us to access a wide range of media types. We can stream all our music and video entertainment. We have continual access to photos of our friends on Facebook, and we can create various "streams" of our own lives through Snapchat and Strava. By 2019, it is forecast that 80% of all traffic on the Internet will be some form of video content [7].

The effects of NN

An online service which uses these new high-data-rate formats may have significantly greater traffic demands than another. Due to the principle of NN, ISPs are unable to discriminate between services in response to the resulting imbalance of network traffic. They must, by law1, treat all (legal) content equally regardless of its source and destination. That’s not to say that ISPs are getting a bad deal from high-bandwidth services, as they are allowed to charge Content Providers (CPs) based on the bandwidth they use. The simple principle of NN makes the Internet a strangely level playing field which, according to Wu, makes it a platform where money can have a limited influence on speech [22].This simple principle makes the Internet fundamentally democratic. It empowers individuals to act free of governments and organisations [14]. If NN laws were to be relaxed, ISPs and governments would be able to control traffic on the Internet, becoming gatekeepers to the knowledge and services we access. ISPs would benefit financially from such a change. Governments and those who influence government decisions would benefit politically. Of course, the parties interested in destroying NN tell us that they just want to make the Internet safer by allowing a handful of organisations to hold complete guardianship over traffic on the net. In recent debates, Ajit Pai has also claimed that American ISPs cannot afford to invest in the infrastructure they provide without changes to NN. This is a surprising claim, given that Comcast’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO) informed investors in December 2016 that the ISP had no concerns with Title II (which contains the Net Neutrality legislation) [8].

As the Internet has matured, it has become more centralised in many ways. The early Internet’s End to End (E2E) principle suggested that functionality should be implemented at endpoints wherever possible, and at network level wherever absolutely necessary [1]. ISPs have disregarded this principle in order to build connecting infrastructure, charging users and CPs as much as they can for access. This has allowed them to make vast profits and has facilitated the use of Internet Traffic Management (ITM) techniques. Many of these are necessary in order to maintain the network, such as protecting against Denial of Service (DOS) attacks and performing protocol-agnostic routing of traffic to keep congestion down. Thanks to the principle of NN, ISPs have not been able to abuse the shift towards centralisation in order to interfere with end-users’ enjoyment [2]. If NN legislation were relaxed, they could capitalise on their new capabilities by charging users to access specific services whilst also invoicing CPs for access or priority access to their customer-base [11].

1: EU law requires NN to be respected except for a few specific circumstances. US laws have protected NN since 2010, but Ajit Pai seeks to repeal the rules set down in the FCC’s Open Internet Order.

The impact of changing NN legislation

According to the models analysed by Reiffers-Masson, Hayel, and Altman, allowing "pricing agreements" between CPs and ISPs would benefit Internet users in providing a better-perceived cost of service [20]. However, they also accept that this would come at a detriment to CPs. Reiffers-Masson, Hayel, and Altman claim that the charging of the two-sided market would reach an equilibrium, but also accept that they have not considered the effects of ISPs interfering with Quality of Service (QoS). They also, in my view, consider an unrealistic model in which users and CPs are exclusive groups. As far as Lee and Wu are concerned, users act as CPs in the sense that all media is "content" [11]. I also feel it is wrong to ignore the detriment that the additional costs would bring to CPs. After all, it is the absence of payments from content creators which has facilitated the entry of many content creators in the first place [11]. Destroying NN would lead to reduced competition and innovation, and ultimately will negatively affect all those who thrive on the open platform.We must also remember that the Internet is a two-sided market, which means it is subject to ’network effects’ - by which an on-line service is more useful to users the more users there are. If users must pay to access specific services, the network-effects are more damaging to start-ups as users are often more likely to avoid a service completely than pay an upfront cost to evaluate its quality [11]. If start-ups are held back from gaining users in this way, then their chances of disrupting an existing market through innovation could be crushed. This can already be seen in some countries where certain on-line services fall under a "zero-rating" category. Users can access websites in this category without using or paying for data towards them. This is often considered a grey-area in the NN debate. Although some countries allow this under NN laws, several have banned the practice on competition and freedom of expression grounds [6].

Conflict of Interest

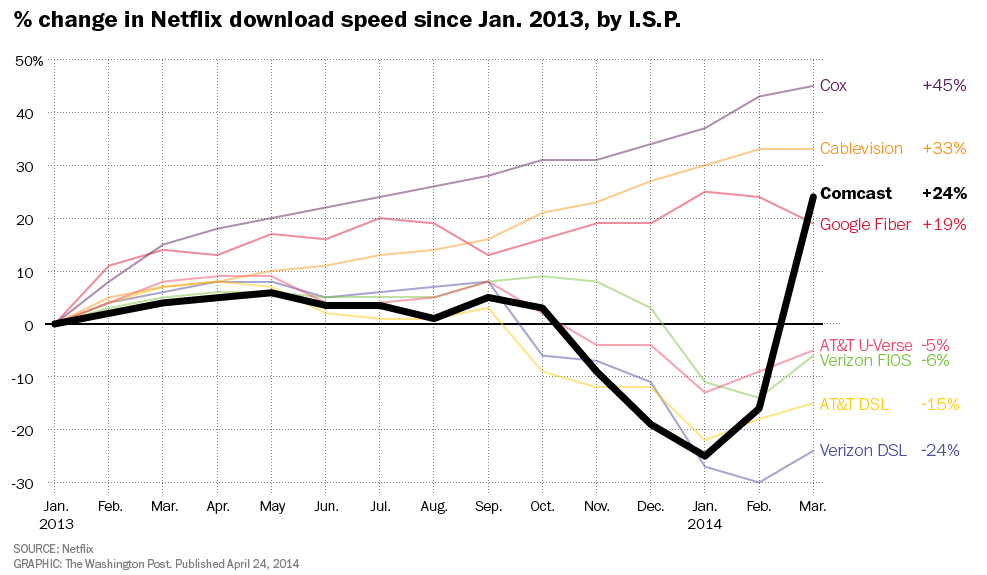

ISPs all have some conflict of interest when it comes to the NN debate. They provide traditional telecommunication products with which modern Internet applications compete. For example, many individuals now use WhatsApp in place of Multimedia Message Service (MMS). If Verizon in the United States (US) were able to degrade user’s WhatsApp experience, then more MMS messages would be sent over their network and phone bills would rise.Similarly, ISPs often have an interest in prioritising one 3rd-party service over another. This could be simply down to which service pays them more or could relate to complicated political matters surrounding the companies. Ajit Pai strenuously denies that any ISP would ever carry out targeted, deliberate degradation of traffic to support their own interests, but it is done even with NN legislation in place. From May 2013, the download speeds for Americans accessing Netflix steadily fell on a number of networks, with several users reporting greater speeds when accessing the service via a Virtual Private Network (VPN)2. In February 2014 when Netflix resolved a dispute with Comcast, their speed was suddenly restored. This can be seen in Appendix A. Evidence of similar conduct by Free - an ISP in France - was seen during negotiations with Google [9].

As well as providing millions of people with opportunities to reach large audiences, freedom on the Internet has broken down barriers to the free flow of information. This has enabled many to enjoy free expression, and democratic participation that would otherwise be impossible [16].

The openness of the Internet has enabled millions of people around the world to become owners in the political process of their country. The damaging effects of ending NN would not only harm the future of the technology itself but also the freedoms that have been won by many [18].

2: Using a VPN prevents ISPs from seeing the true source and destination of a user’s packets, which prevents them from treating traffic differently based on which service is being accessed.

Conclusion

Throughout history, whenever a new communication technology has been invented, it has always become less open during a process of consolidation by organisations who want power over the industry [24]. In many countries, governments have greatly enjoyed these monopolies is it provides them opportunities for mass intervention [24]. This is evident from the nature of illegal mass-surveillance operations that the US and United Kingdom (UK) carried out with the help of a number of large companies including Google, Facebook, and Apple [15].If we allow ISPs to become gatekeepers of traffic and content on the Internet, they will be able to corrupt a system which currently allows users to freely connect with vast audiences. In doing so, they will gain total control over our communication, resulting in ISPs having unprecedented economical, social and political influence. It is important to protect NN globally, as the Internet is a global resource. Failing to protect NN in one country would have a huge knock-on effect for the rest of the world. For this reason, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has condemned the attack on NN.

The Internet is not currently broken. It fosters free-speech and creativity. Fundamental changes to the architecture of the Internet would risk damage to healthcare advances, trade, innovation and social well-being. Furthermore, abandoning NN could deny millions of individuals basic rights enjoyed by Internet-users around the world.

References

[1] "Net Neutrality Compendium: Human Rights, Free Competition and the Future of the Internet". ISBN: 978-3-319-26425-7.[2] Belli, Luca. "End-to-End, Net Neutrality and Human Rights". ISBN: 978-3-319-26424-0. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-26425-72. URL: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-26425-72.

[3] "Net Neutrality Compendium".

[4] "Net Neutrality Compendium".

[5] "Net Neutrality Compendium". ISBN: 978-3-319-26424-0. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-319-26425-7. URL: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-319-26425-7.

[6] Cho, Soohyun and Qiu, Liangfei. "Less Than Zero? The Economic Impact of Zero Rating on Content Competition". In: In: SSRN Electronic Journal (2016). DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.2844930. URL: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=2844930.

[7] "Cisco Visual Networking Index: Forecast and Methodology, 2016-2021".

[8] "Edited Transcript: CMCSA - Comcast Corp at UBS Global Media and Communications Conference".

[9] Economist, The. "An ad-block shock: France V Google". URL: https://www.economist.com/news/business/21569414-xavier-niel-playing-rough-internet-giant-france-v-google.

[10] Foditsch, Nathalia. "Zero Rating: Evil or Savior? Data Access and Competition Aspects".

[11] Lee, Robin S and Wu, Tim. "Subsidizing Creativity through Network Design: Zero-Pricing and Net Neutrality". In: In: Journal of Economic Perspectives (2009). DOI: 10.1257/jep.23.3.61. URL: http://pubs.aeaweb.org/doi/10.1257/jep.23.3.61.

[12] Lemley, Mark A and Lessig, Lawrence. "The End of End-to-End: Preserving the Architecture of the Internet in the Broadband Era".

[13] Lessig, Lawrence. "What Things Regulate Speech".

[14] Lessig, Lawrence. "The Internet under Siege".

[15] Loideain, Nora Ni. "EU Law and Mass Internet Metadata Surveillance in the Post-Snowden Era".

[16] McDiarmid, Andrew and Shears, Matthew. "The Importance of Internet Neutrality to Protecting Human Rights Online".

[17] McDiarmid, Andrew and Shears, Matthew. "The Importance of Internet Neutrality to Protecting Human Rights Online".

[18] Musiani, Francesca and L{\"o}blich, Maria. "Net Neutrality from a Public Sphere Perspective".

[19] OECD. "Economic and Social Benefits of Internet Openness". DOI: 10.1787/5jlwqf2r97g5-en. URL: http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/science-and-technology/economic-and-social-benefits-of-internet-openness_5jlwqf2r97g5-en.

[20] Reiffers-Masson, Alexandre and Hayel, Yezekael and Altman, Eitan. "Pricing Agreement between Service and Content Providers: A Net Neutrality Issue".

[21] Taylor, Linnet. "From Zero to Hero: How Zero-Rating Became a Debate about Human Rights".

[22] Wu, Tim. "Network Neutrality: Competition, Innovation, and Nondiscriminatory Access". In: In: SSRN Electronic Journal (2006). DOI: 10.2139/ssrn.903118. URL: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=903118.

[23] Wu, Tim. "Network Neutrality: Competition, Innovation, and Nondiscriminatory Access".

[24] Wu, Tim. "The Master Switch: The Rise and Fall of Information Empires". ISBN: 9780307269935. URL: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=tKr0QwAACAAJ.

Copyright

Most of my photos are licensed under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0.If you are unsure about your right to use them please contact me.